Asana: The 3rd Limb of Patanjali’s Path to Freedom

This series will build on our introduction to Patanjali’s Eight Limbs of Yoga and dive deep into each limb or step on the yogic path to liberation. This article will focus on the third limb – Asana. Before we dive in, let’s look at the Eight Limbs system briefly as a reminder.

The Eight Limbs of Yoga

The Eight Limbs of Yoga is a system of morals and techniques that helps calm the mind and stop the internal chatter. Mastery of the mind is the way we dissolve the ego and attain Moksha (liberation).

The Eight Limbs of Yoga are:

- Yama

- Niyama

- Asana

- Pranayama

- Pratyahara

- Dharana

- Dhyana

- Samadhi

Understanding Asana Within Yoga

In the west, we are probably most familiar with the limb of asana – the physical postures we know as yoga. Many of us practice Hatha yoga – a branch of the Yoga Tree that focuses primarily on asana and pranayama. Other styles, such as Ashtanga, Iyengar, and Vinyasa flow yoga, still come under the branch of Hatha yoga – the yoga of the body. Patanjali’s Eight Limbs of Yoga comes under the branch of Raja yoga, and within that asana is a component but not the main focus, as with Hatha yoga.

The Yoga Tree shows the different types of yoga we can practice to achieve liberation; Hatha yoga is just one yogic path.

The Yoga Tree Branches

- Hatha yoga (primarily asana and pranayama – the yoga of the body)

- Jnana yoga (the study of the scriptures – the yoga of the mind)

- Bhakti yoga (devotional practice – the yoga of the heart)

- Karma yoga (service-based action – the yoga of selflessness)

- Tantra yoga (sacred ritual – the yoga of divine feminine energy/Shakti)

- Raja yoga (Patanjali’s Eight Limbs of Yoga – the yoga of transcendence)

Asana as the Third Limb

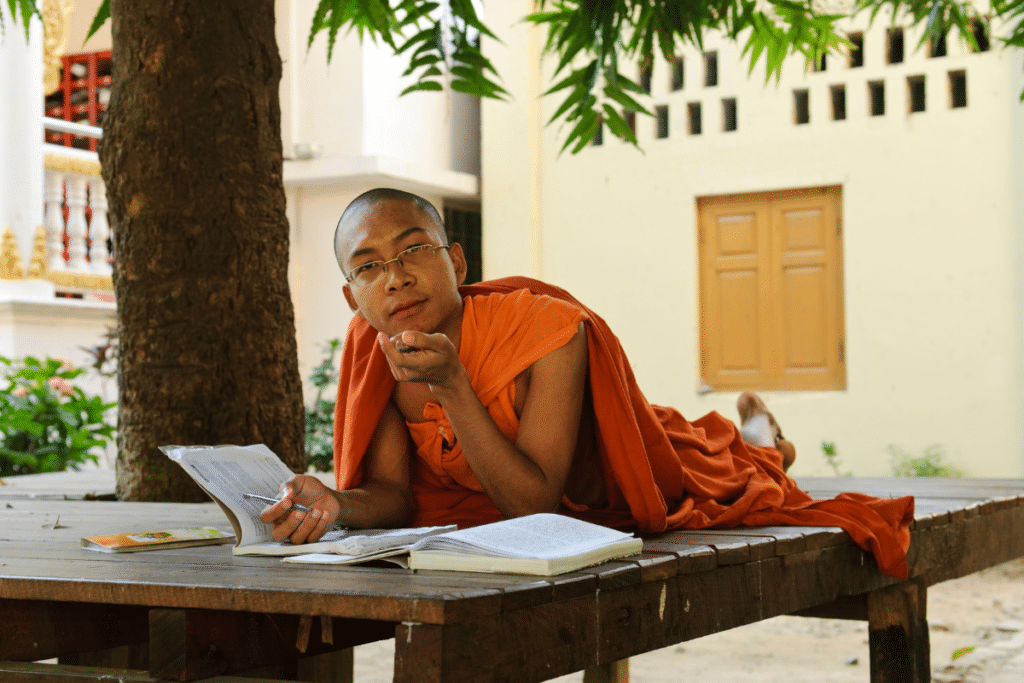

The original purpose of the asanas in Patanjali’s system was not to sculpt the body or achieve particular postures but to prepare the body for long periods of meditation. When the body is supple, the yogi can remain still for extended periods in comfort, with focused attention on meditation and reflection.

“Sthira sukham asanam.”Sutra 2.46 of ‘The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali.’

‘Sthira’ means strength, stability, or effort. ‘Sukha’ means ease or comfort. We can translate the phrase “sthira sukham asanam” as ‘a stable and comfortable posture.’ It is the perfect balance between effort and ease.

The practitioner should sit in a comfortable pose that maintains an alert yet relaxed posture. In doing so, we reduce the risk of the muscular pain and stiffness that can cause restlessness and discomfort, and we become more focused and present in the practice. This allows us to go much deeper into meditation. Also, a dedicated asana practice develops focus, concentration, and discipline – all crucial assets for an effective meditation practice.

Asana for Health and Vitality

The ancient yogic sages viewed the body as a temple for the spirit, and they were right. Good health is the foundation for spiritual growth – we cannot expect to move forward with our spiritual practice if we are unhealthy or sick. Ill health serves as a distraction from our meditation practice and takes up a considerable amount of energy. Think about it, the last time you were sick – did you feel like doing your yoga and meditation practice?

It is imperative that we create health by nurturing the body with nourishing foods, pure water, proper sleep, and daily movement. Physical yoga practice helps to build strength, stamina, stability, and flexibility. Additionally, the postures work on our internal bodily systems as well as the muscles, joints, and ligaments. They also balance the endocrine system, help to flush toxins out of the body via the lymphatic system and condition the circulatory system.

Two Types of Asana

The postures can be broadly split into two main types: active and meditative. The active postures condition and stimulate the body, and develop strength and stamina. The meditative postures create length, space, and flexibility. Let’s look at some examples of each type.

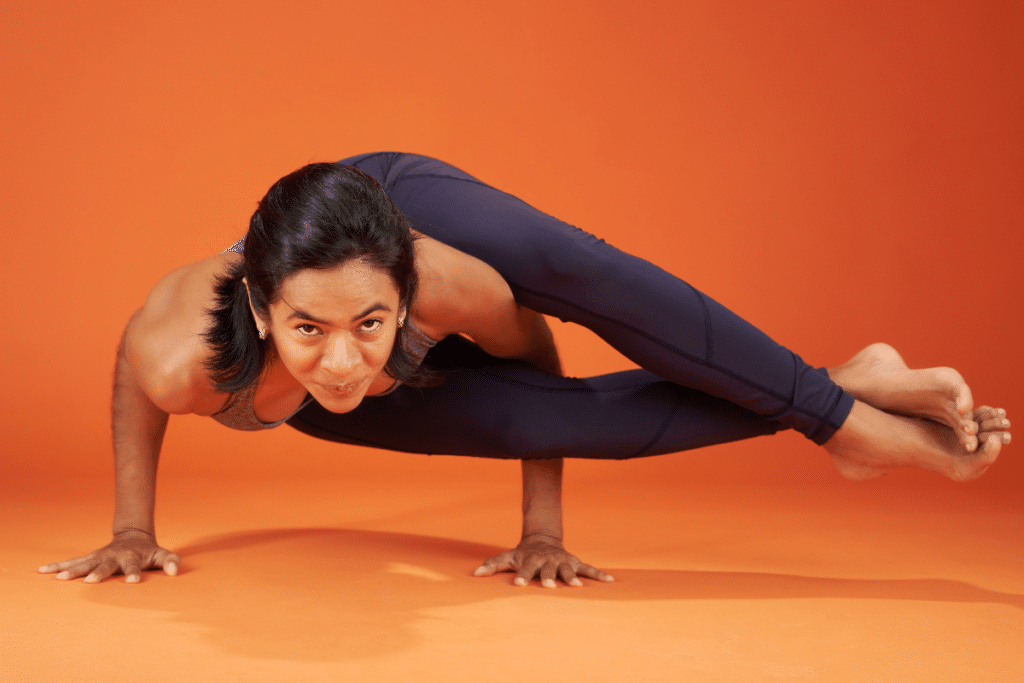

Active Postures

Active poses condition the body, both internally and externally. They help to build strength in the muscles, stimulate the cardiovascular system, and strengthen the connection between the muscles and the nervous system. They are the yoga poses that get the heart pumping, the body moving, and the muscles working!

Additionally, active poses utilize active stretching – using your body’s own strength and power to facilitate the movement. The muscles engage and contract to cause the opposite muscles to stretch and release. In this way, active stretching also builds strength.

Some examples of active yoga poses and flows are:

- Surya Namaskar (Sun salutations)

- Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward facing dog)

- Utkatasana (Chair pose)

- Garudasana (Eagle pose)

- Utthita Trikonasana (Extended triangle pose)

- Natarajasana (Dancers pose)

- Parivrtta Parsvakonasana (Revolved side angle pose)

- Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-limbed staff pose)

- Virabhadrasana (Warrior pose)

Meditative Poses

These postures are great for helping the body to soften, lengthen, and open. They are also known as passive poses, not because they aren’t as good, but because they involve passive stretching. Passive stretching is generally better for building flexibility than active stretching, which is why these postures are also called meditative poses.

That is not to say you will necessarily feel comfortable enough to sit for extended periods of meditation straight away. But practicing these poses on a regular basis will help you to develop the flexibility and openness needed for comfort in longer meditation sessions.

Passive stretching involves no input from the muscles – it uses outside forces such as bodyweight, props, and gravity to enable the stretch. Yin yoga uses passive stretching, which is why it is the best type of yoga for flexibility.

Some examples of meditative or passive poses are:

- Balasana (Child’s pose)

- Eka Pada Raja Kapotasana (One-footed king pigeon pose)

- Viparita Karani (Legs up the wall pose)

- Supta Baddha Konasana (Reclined butterfly pose)

- Virasana (Hero pose)

- Supta Padangusthasana (Reclined hand to big toe pose), using a strap

- Gomukhasana (Cow-faced pose)

- Malasana (Garland pose)

- Padmasana (Lotus pose)

- Savasana (Corpse pose)

Kaya Mudra

The other primary purpose of asanas was that when combined with pranayama and dharana, they form full-body mudras (kaya). A mudra is a gesture that provokes a particular energy, much like a mantra. By using mudras, we channel the energy in a specific way and for a particular purpose.

You are probably already aware of hand mudras (hasta), such as Chin (Gyan) mudra – where the thumb and index finger touch to create an energetic circuit. Another well-known hasta mudra is Anjali mudra – also known as Namaste, because the palms are brought together in front of the heart center.

Kaya mudras relax the nervous system, improve respiratory function, and direct the flow of prana within the body. They also help to increase concentration and focus and so result in deeper meditative states. Some of the passive or meditative yoga postures are also kaya mudras when combined with pranayama and concentration. The difference between practicing asana and kaya is that the latter focuses more directly on the generation and movement of prana within the chakras and nadis.

Some examples of kaya mudras are:

- Viparita Karani (legs up the wall pose – balances Ida and Pingala nadis)

- Yoga mudra (Full lotus with forward fold and arms crossed behind the back, increases dharana – concentration)

- Manduki mudra (Frog gesture – activates Muladhara chakra)

- Sharnagat mudra (Balasana with arms outstretched – stimulates Anahata chakra and Sushumna nadi)

Practicing Asana in the Context of the Eight Limbs

As you can see from our exploration so far, the physical practice of yoga postures is not the primary focus of Patanjali’s path to liberation; it is just one step on the journey. We need to balance our asana practice with all the other pieces of the yoga puzzle because physical poses alone are not enough to bring us to the self-realization or pure awareness that leads to Moksha.

Next time you are in class, bring to mind Patanjali’s instruction: “sthira sukham asanam.” Analyze whether or not you are experiencing the pose in these terms. Do you feel strong and stable, yet open and comfortable? Have you struck the correct balance between effort and ease? Or are you pushing too hard into the posture?

The best way to know if you are forcing yourself too far is to check in with your breathing. Has your breath become shallow or labored? If so, back off slightly and explore where the edge between effort and ease lies for you in this pose.

Another clue that you are forcing instead of surrendering into the pose is muscle shaking. If you notice your muscles trembling, ease off the stretch slightly. Of course, it is important to feel a stretch, but don’t overstretch the muscles. Overstretching and forcing to the point of shaking is counterproductive anyway because when the muscles feel in danger, their reaction is to tense to prevent injury of tearing.

That is why utilizing yin yoga poses with props, passive stretches, and longer holds is far better for your flexibility. When the muscles feel safe and supported, they will open and relax, allowing you deeper into the posture. Next time you find yourself overstretching or forcing, back off, soften, relax, and exhale into the stretch. See if you can find the point of surrender where you can strike that delicate balance between stability and ease. That is the art of asana.

Balance Asana with Other Techniques

It is vital to ensure that you develop a healthy blend of asana, pranayama, and meditation. In the west, we are culturally so focused on the physical aspect of the practice, that the others sometimes get left behind. Even if you only have a set amount of time for your practice, see if you can find some ways to broaden out from purely posture-based sessions.

For example – can you begin your home practice session with 5 minutes of pranayama and end with 10-15 minutes of meditation? Or perhaps you would prefer to bring pranayama into your morning routine and meditate before bed each evening? Find a way to prioritize all the practical elements of the system.

Conclusion

We hope you have enjoyed this guide to the third limb of Patanjali’s system and have gained some useful knowledge to take forward into your practice. Ensure you subscribe to our newsletter so that you don’t miss the remaining articles of this series on Patanjali’s Eight Limbs of Yoga. If you missed the first two articles in this series, here they are:

The 5 Yamas of Yoga: Universal Morality

The 5 Niyamas of Yoga: Personal Behavior

The experts at Femigod are here to answer your questions, so place them in the comments box below or post them in our Sacred Circle forum. The forum is an excellent resource where you can connect with fellow Goddesses for support and inspiration, as well as the Femigod team. We would love to chat with you there.

[…] Asana: The 3rd Limb of Patanjali’s Path to Freedom […]

[…] Asana: The 3rd Limb of Patanjali’s Path to Freedom […]

[…] Yoga asanas that are particularly good to help balance your root chakra are: […]

[…] yoga is based on the classical Hatha yoga asanas, which are used for a prior body warm-up, instead of doing it the other way around, as it is […]

[…] Margo Schaefer April 28, 2023 1 Comment […]